Their Last Resort Was to Stop Breathing

One of the less talked about problems among Afghan youth is committing suicide. Relatives think several factors played into their loved ones ending their lives.

Reporter’s name held for safety, edited by Mohammad J. Alizada, & Brian J. Conley

If you or someone you know maybe considering suicide, contact the international suicide prevention resource center here, and Open Counseling here. We are not aware of any organizations providing suicide prevention resources directly to Afghans, therefore please contact the country closest to you for help.

If you are aware of Afghanistan-based resources or organizations specifically working on suicide prevention with Afghans, please let us know.

Alive-in is a not-for-profit media agency that mentors journalists from underrepresented communities to increase local and international understanding. Subscribe to receive our stories directly in your inbox.

NILI — Daikundi is a predominantly Hazara region that became a province in 2004. Hazaras are the third largest ethnic group in Afghanistan, after Tajiks and Pashtuns. The Taliban, a group made up primarily of Pashtuns–Afghanistan’s largest ethnic group–have been in conflict with the Hazaras throughout the last three decades, subjecting them to discrimination, death, and imprisonment.

According to the World Bank, suicide mortality rate in Afghanistan was 4.1 per 100,000 in 2019. Globally the suicide mortality rate is reported to be 9.2 per 100,000 population. Although Afghanistan has historicall had a relatively low suicide rate, residents of Daikundi say that suicides are up since the Taliban seized power.

Eight people, mostly youth and predominantly girls, died by suicide in the past ten months in Nili, the capital of central Daikundi province. Their families believe several factors led to the deaths of their loved ones: fear of Taliban rule, psychological trauma, abuse, girls losing the opportunity to seek education and work, poverty and neglect.

Residents of Daikundi’s provincial capital told Alive in Afghanistan they are shocked by the number of youth committing suicide. Prior to Afghanistan’s economic and political collapse human rights organizations tracked suicide statistics. Although suicide is an important public health issue, these organizations are no longer able to track suicides across the country.

Over two months Alive in Afghanistan investigated several suicides in Nili, Daikundi. These findings are not a comprehensive list of suicides in the area, there may be many more. This article is but one effort to shine a light on the impact of suicide in Afghanistan, a problem that due to cultural norms is often overlooked or ignored.

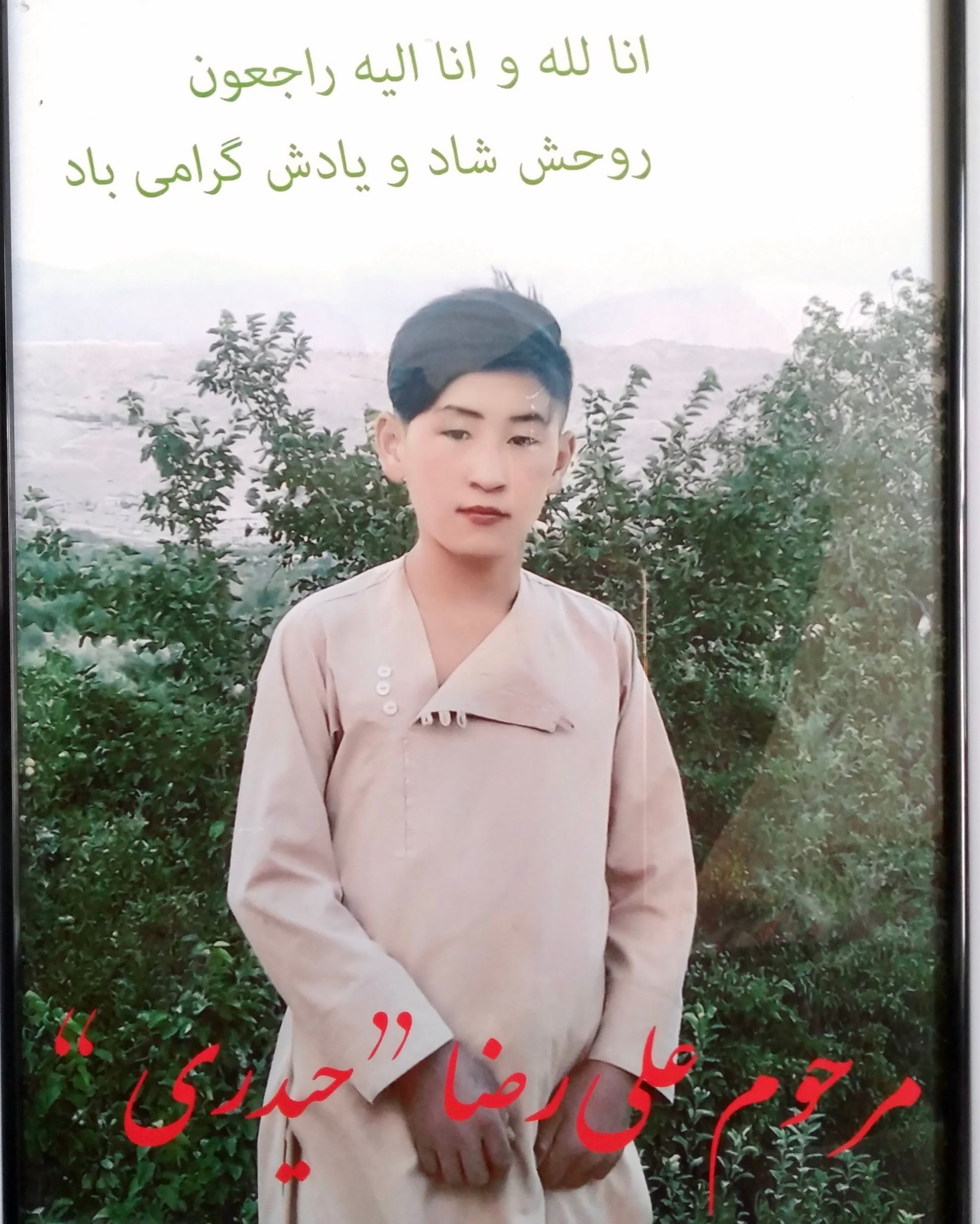

Ali Reza, a 14-year-old resident of Sar-e Nili village, died by suicide three days after the Taliban took control of the province. Zahra Haidari, Ali Reza’s mother, told Alive in Afghanistan, “Ali Reza had climbed a tree in front of our house the day before his death, his father asked him to come down, but Ali Reza said he preferred to fall and die rather than being killed by the Taliban.”

According to Ms. Haidari, her son had taken a selfie with some members of the Taliban in Nili on the day the Taliban took control of Daikundi. Ali Reza told her the experience was very scary, but whether that incident lead directly to his death remains unclear.

According to Ms. Haidari, her family had not taken Reza’s words seriously. The next night, Reza did not join the family for dinner. Thinking he may have gone to the village mosque for prayer, they sent his brother to search for him, but they didn’t find him in the mosque or anywhere around the village. Later that evening they found him at home, having committed suicide.

“Ali Reza was very sensitive, he took everything to heart. He was the youngest in our family of seven.”

Ms. Haidari said she feels guilty for not looking after her son and not taking his words seriously. “Maybe the presence of the Taliban was much more terrifying for my son than we thought.”

Zakia Jawadi, 19, died by suicide during the first week of the Taliban’s takeover. The reason she took her life is still not clear but Masooma Jawadi, Zakia’s mother, regrets being unable to help her daughter.

“I didn’t know what to share or what to keep to myself when it came to my children. I always talked to her about suffering and pain and I think that was a heavy burden on her,” Masooma told Alive in Afghanistan.

Zakia’s grandfather died early last year and her uncle also had family issues, which are things that Masooma shared with her daughter.

According to Ms. Jawadi, Zakia spent her time off studying in her room but lost her hope of education following the Taliban takeover. Zakia gathered all her tighter, more figure-hugging clothes, and jeans, put them in one bag, and hid them away.

The Taliban banned girls from seeking education and restricted women from the workplace following their victory. Girls across Afghanistan are barred from going to school above 6th grade.

To learn more about the Taliban’s restrictions, read Alive in Afghanistan’s articles on education, and women.

“Every day there is at least one or two women who commit suicide for the lack of opportunity, for the mental health, for the pressure they receive[,]” Fawzia Koofi, former deputy speaker of the Afghan Parliament said during at a UN rights forum in Geneva on Friday last week.A UN Development Program (UNDP) study published in September of last year said as much as 97 percent of the Afghan population was at risk of sinking below the poverty line by the middle of 2022. Although it is now July 2022, AiA found no additional reporting from UNDP.

In another case, Basgul Seddiqi, a 21 year-old girl killed herself two months after the Taliban took over Afghanistan.

Basgul was a second-year student of mining engineering at the University of Bamiyan, a neighboring province. Occasionally there was conflict over university fees between Basgul and her sister Nazanin who studied at Kandahar University. Their family did not have enough to cover the fees for both girls so Nazanin would ask Basgul to take off for a term so one of them could finish school, otherwise they would both be left behind, which was a source of argument between the siblings.

Basgul’s father paid for her and her other siblings’ education through his work as a farmer, which he had done for most of his life. Unfortunately, the persistent drought over the past several years has meant less revenue from farming and less money for their family.

“Despite having many suitors, Basgul did not intend to marry. My daughter regretted not having her desired home, telling me once – I feel ashamed, I can't even invite my friends into this house," Basgul’s mother told Alive in Afghanistan on the condition of anonymity. According to her, Basgul was not happy with their situation and the life they had.

On the night Basgul killed herself, she ate more than usual, after that, she watched a movie on her computer before leaving the house. The next morning, they found Basgul had hanged herself with her own scarf from a tree outside their home.

25 year-old Amir Gul Karimdad and 12 year-old Mohammad Ekhtiari also died by suicide in Nili District after the Taliban took over.

Hafiza Ashghari, a 17 year-old newlywed, committed suicide three months after her wedding and just days after the Taliban took over Daikundi. According to Hafiza’s mother, Hafiza couldn’t go to school due to the large number of responsibilities she had after she moved in with her husband’s family.

“She cooked for 11 people in her new family and her problems grew by the day, leading her to end her life so that she can free herself from those shackles,” said Hafiza’s mother, who spoke to Alive in Afghanistan on the condition of anonymity.

If you are able to support our work financially, please click the button below.